Claylands gate (credit: M. Watson)

About the South Norfolk Claylands

Once, the South Norfolk Claylands' unique landscape was filled with wildlife. But, over time, due to changes in land management, increased development and the impacts of climate change, sadly a great many vital habitats have disappeared.

We want to restore the important habitats found across this unique landscape to help our wildlife thrive.

By working with communities in the area to create habitats such as hedges, ponds and meadows we’ll help more wildlife find food and shelter. We will also provide routes to help creatures such as hedgehogs, newts, and bats move across the landscape, helping them to be more resilient to challenges, including those presented by our changing climate.

We’re also creating new ways for the communities that live here to thrive too – by supporting the local economy and providing opportunities for people to enjoy and help the wildlife on their doorstep.

Windmill in Claylands (credit: M. Watson)

Claylands landscape history

Learn more about the history of the ClaylandsAn ancient landscape

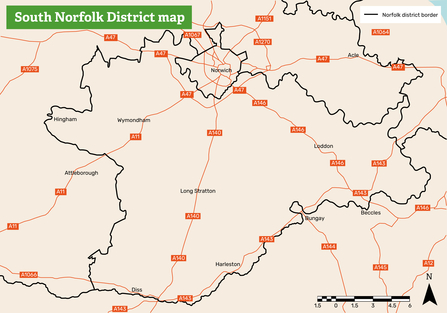

The South Norfolk Claylands form part of the East Anglian Plain – a distinctive landscape found on a belt of boulder clay that lies over chalk and runs through Suffolk and south-east Norfolk. Land use in the South Norfolk Claylands is mainly arable, with scattered woodlands. It is an area noted for its ancient landscape, characterised by high hedges, pollarded trees, and open fields and commons.

The Claylands area is a relic of glaciation from about 480,000 years ago, when an ice sheet moved south across eastern England, eroding chalk and Jurassic clays along its path. The ground-up deposits left by the ice formed a chalky boulder clay soil, interspersed with areas of fine sand and gravel. This variation in soil can be seen in the flora of grasslands and in woodlands that are home to a number of key species, such as sulphur clover and turtle doves.

Over time, habitats have changed. Ancient meadows have been converted to arable fields; trees, hedgerows and ponds have been removed to make way for more intensive farming and development. Relict habitats remain but are patchy and fragmented across the landscape. Habitat loss and fragmentation can reduce the size of wildlife populations and hinder their movement between increasingly isolated habitats, threatening the future of certain species.

The key to reversing these trends is improving and restoring connectivity between relict patches of habitat. By improving our understanding, then taking targeted action to restore features such as ponds, hedges, meadows, and woodland, this will create new 'stepping stones' of habitat and wildlife corridors. In turn, these connected habitats will allow species to more easily and safely move through our countryside, improving their long-term prospects for survival.

View our past and current Claylands projects below.