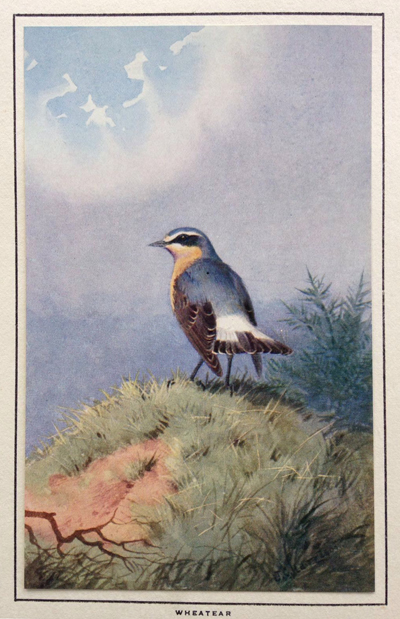

In 1939 the Christmas card sold to raise funds for Norfolk Naturalists Trust featured a wheatear painted by J. C. Harrison. With it went a note: ‘This bird has been chosen because it was a favourite of the late Dr. S. H. Long, the founder of the Trust and its Honorary Secretary for twelve years. No one looked forward more eagerly than he to the arrival of the Wheatear in early spring of each year and he was usually the first to record its appearance in Norfolk. The Trust has recently entered into arrangements to acquire an area of Breckland, where this bird nests, in order to preserve the land as a Sanctuary, and on this site it is proposed to erect a stone in memory of Dr. Long.’

Sydney Long had died on 15 January 1939, having become ill in December. The stone erected for him still stands today, on our nature reserve at East Wretham Heath. A little to the south of Langmere, it is a quiet memorial among the birches to a quiet man who changed the course of wildlife conservation in the UK.

Wheatear by JC Harrison

Before his death, aware of the uniqueness of the Brecks landscape and its wildlife, and alarmed by the dramatic pace at which they were being surrendered to forestry, Sydney Long had cherished a desire for Norfolk Naturalists Trust (known since 1994 as Norfolk Wildlife Trust) to protect remaining habitat here. To this end in 1932 NNT bought three cottages in Lakenheath. The move bestowed on NNT commoners’ rights over Lakenheath Warren and meant in theory it could veto development of this exceptional site. This conservation coup was reported in The Times on 18 April 1933 in these words: ‘Ever since the Forestry Commissioners have raided the Breckland district of Norfolk and Suffolk, where some 30,000 to 40,000 acres have already been planted, there has been a strong feeling among members of the trust and others that at all costs the stone curlew must not be driven away from this its stronghold in England as was the great bustard in the early years of last century. But how to effect this object remained unsolved until a few months ago, when it was very ingeniously surmounted by the trust.’ However, among the many global tragedies of the Second World War, a tragedy for wildlife conservation in the Brecks was the requisition of Lakenheath Warren and its conversion to an airbase; the familiar airbase which occupies the site still today.

Thus, by the time of Sydney Long’s death in January 1939 NNT had acquired no nature reserves in the landscape he loved. Shortly afterwards, however, as noted in the Christmas card of that year, East Wretham Heath became our first Brecks reserve. Two further land acquisitions quickly followed here to complete a reserve of 360 acres, embracing the rare fluctuating meres known as Langmere and Ringmere.

No one looked forward more eagerly than he to the arrival of the Wheatear in early spring of each year and he was usually the first to record its appearance in Norfolk.

1939 NNT Christmas Card

According to the Report of the Council published by NNT in April 1941, it was not at the time deemed necessary to appoint a full-time warden but, ‘an arrangement has been made with a reliable warrener living in the district whereby he has undertaken to keep the boundary fire-trace clear and to look after the nesting birds in the summer in return for the rabbiting.’ Finding a reliable warden who would work in return for rabbits might prove trickier today!

Shortly after the purchase of East Wretham, Christopher Cadbury, who would become one of NNT’s most committed donors and fundraisers, offered significant financial support for the purchase of the first reserve at Weeting Heath. Thanking Cadbury, the Report of the Council, April 1942, describes the land: ‘Apart from its peculiar natural beauty this breck is in every way most desirable as a Nature Reserve and in particular as a Bird Sanctuary. It has also archaeological interest.’ The following year these 300 acres were acquired, for their rare Breck flora and nesting birds, including what were then known as Norfolk plovers (stone curlews) and green plovers (lapwings). Both species still nest at Weeting today.

Christopher Cadbury’s commitment to the preservation of Brecks wildlife by no means ended there. The Report of the Council, May 1945, records: ‘During the year, as the result of a generous gift from Mr. Christopher Cadbury, the Breckland Reserve at Weeting has been enlarged, and its value much increased by the addition of a further seventy acres. […] This breck is not only of special ornithological interest but is also of outstanding archaeological importance. There are indications that it is the site of a Roman farm and pieces of Roman pottery are frequently unearthed, while flint tools of the Neolithic period point to much earlier human occupation.’ In 1949 he expanded NNT’s presence in the region yet further with the donation of some of the most important remaining Breck grassland on 225 acres of Thetford Heath, purchased from Lord Iveagh.

A Brecks innovation in 1970 was the creation of an arable weed reserve adjacent to Weeting Heath as a refuge for the annual plant species which depended, nationally, on the disturbed soils of traditional agriculture in the region. The Annual Report for 1970 reads, ‘Seeds and plants of many of the Breckland rarities were introduced during the year and it is planned to build up a large collection for both experimental and transplant purposes.’ The reserve still exists and remains home to many rare arable plants including spring, fingered and Breckland speedwells and field wormwood.

The exceptional reserve at Thompson Common came into the care of NNT in 1981. It is famed for its hundreds of pingos, strange ponds which are at once ancient and modern. Until some 12,000 years ago, the Devensian ice sheet, the last great glaciation of the Ice Age, covered North West Norfolk but stopped in a line from Heacham to Stiffkey, with the rest of Norfolk seasonally frozen but not covered in ice. As springs rose here from the underlying chalk their water froze and expanded beneath the ground to create ice-cored hillocks. To the Inuit, in whose arctic lands many such small frozen hills pertain today, these are known as pingos. In English the word has come to describe the ponds which are left when the ice melts.

Though as ancient as the post-glacial landscape of the UK, the pingos are highly significant for the wildlife of the modern Brecks. Their chalk springs have flooded them through millennia, ensuring a place to live and breed for their rare and specialised wildlife. At Thompson Common 58 threatened species are known to inhabit the pingos, with small snails and water beetles prominent among them. Thompson’s pingos are also the national stronghold of the scarce emerald damselfly, which was once considered extinct in the UK.

Another remarkable feature of these rare ponds lies in their muddy bottoms. Layers of silt here contain pollen grains, snail shells and beetle wing cases accumulated over millennia from highly sensitive species with precise habitat needs. These allow scientists to see how climate and vegetation have changed since the Ice Age and inform today’s management of this precious reserve. The pingos and surrounding grassland and scrub are managed, by staff, volunteers and livestock, to create a patchwork of microhabitats, offering a home to each of the specialised plants and animals which depend on them.

Indeed across Breckland, the health of habitats for wildlife is improving under new initiatives. In 2001 NWT entered a partnership with the Forestry Commission and Natural England, enabled by the Heritage Lottery Fund, to restore seven sites in Thetford Forest from conifer plantation to grass heathland. The partnership continues today as the Brecks Heath Partnership; it has recently embraced two new sites, and most of its restored grass heaths are now of nature reserve quality, some supporting national rarities such as Spanish catchfly and proliferous pink.

Another exciting recent development in conservation in the Brecks is Breaking New Ground, an alliance of many partners which include Norfolk County Council, the University of East Anglia, the Forestry Commission, and Norfolk and Suffolk Wildlife Trusts. The title Breaking New Ground honours the very name of the region: Breck means broken ground, in reference to the patches of bare earth left historically by shifting agriculture on poor soils, extensive grazing and by countless millions of rabbits. This bare ground was the home of many of the country’s rarest species, including annual plants, specialist moths and solitary bees, but it was lost on a massive scale with the planting of conifers, the introduction of myxomatosis and the arrival of chemical fertilisers and intensive agriculture. One of many initiatives of Breaking New Ground is the Ground Disturbance project which is again opening patches of bare earth on remaining Brecks grass heaths, to favour these rare species of the shifting Breckland sands.

.jpg.aspx?width=600&height=450&ext=.jpg&ext=.jpg)

Pool frogs being released at Thompson Common, photo by ARC

Elsewhere Breaking New Ground, in collaboration with Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, has reintroduced pool frogs to pingos in a secluded area of NWT Thompson Common. Though historically considered an introduction, the pool frog was recently proven by genetic and acoustic research to be a Norfolk native, most closely related to highly threatened Scandinavian pool frogs but stranded in the UK with the retreat of the Devensian glaciation. Tragically the pool frog was lost from Thompson Common, its last native site in the UK, in the early 1990s, as a result of water abstraction from surrounding land and the gradual encroachment of the pingos by scrub. In 2015, however, the first Scandinavian pool frogs (from a secret Norfolk location to which the species had previously been reintroduced) were brought home to restored pingos at Thompson Common.

Sydney Long’s wheatears have now all but disappeared as a breeding species in Breckland, and in Norfolk. However, whereas at the end of his life the Brecks and its wildlife seemed doomed, today, thanks to our donors’ generosity and vision, and collaboration with many partners, the region’s wildlife is returning, frog by frog, pingo by pingo, turf by broken turf. Sydney Long and Christopher Cadbury were right about the significance of the Brecks: fully 28% of the UK’s Biodiversity Action Plan species are found in the region, making it one of the most important for rare wildlife in the country. The legacy of these tireless men is to be found in the Norfolk plovers which still wail on warm evenings at Thetford and Weeting Heaths, in the pool frogs which again sing from ancient pingos on Thompson Common, in the spiked speedwell and maiden pink which yet bloom on Weeting’s beauteous sheep-grazed heath, and in the nightjars which churr from the edge of the pines at East Wretham. And to them every lover of Norfolk’s unique wildlife is grateful.